I'm an unabashed baseball guy. It's in my blood, both sides of my family; and even though there are years where my interest waxes and wanes, baseball is always there like an old friend just a phone call away--no matter how long it's been, we can pick up right where we left off. It's a cultural, liturgical, and even literary phenomenon that sees every batter an Odysseus on a journey of return, and every defense seeking to embody the sentiment that you can't go home again. But the most interesting thing about baseball, I think, isn't the symbolism of the one standing against the many, the hero's journey home, or the personalities and grudges that make some games more or less meaningful for more or less arbitrary reasons. For me, it's the meta-narrative of seasons, organizations, and generations of identity built on innumerable, infinitesimal wins and losses.

Case in point: for over a century the Chicago Cubs built an identity summed up in the phrase, "just wait 'til next year." That simple phrase speaks volumes about not only the men who wore the uniform from 1909 to 2015, but about the organization itself, and even the fans who would follow such a team. What kind of fools go back year after year, decade after decade, loyal to a team that offers no better than an I.O.U. for victory? The phrase is a tacit admission of current failure, an expression of a hope that offers no hard evidence based on track record, and yet compels the faithful to continue pouring their time, emotions, and resources into the promise of a better tomorrow. Friends, if that's not a form of religion, I don't know what is. I say that not particularly to criticize, but merely to observe and wonder--not all teams are able to cultivate an image that so purely captures the need people have to believe in something they have difficulty imagining.

I say it's difficult to imagine the Cubs winning the World Series because for long stretches of more than a century, they didn't offer even the sniff of winning. The Cubs didn't see the postseason from Armistice Day to Black Tuesday. Though they made the Series a handful of times during the Depression (let's be honest--times were bad, the last thing folks needed was the Cubs piling on by being awful), the last troops returning home from the South Pacific in 1945 would have just missed their last chance to see the Cubs in postseason play until the middle of the Reagan administration. No matter--just wait 'til next year. As if to add insult to their injury, in the intervening period, baseball expanded the postseason, such that winning the regular season was no longer an automatic ticket to the Fall Classic. And with each new hurdle to the crown, new and bold possibilities for futility sprang up. New scapegoats emerged (that joke's okay now, they broke the curse), and like Steve Bartman they were wounded and sent off into the wilderness to atone for the sins of nine (at a time).

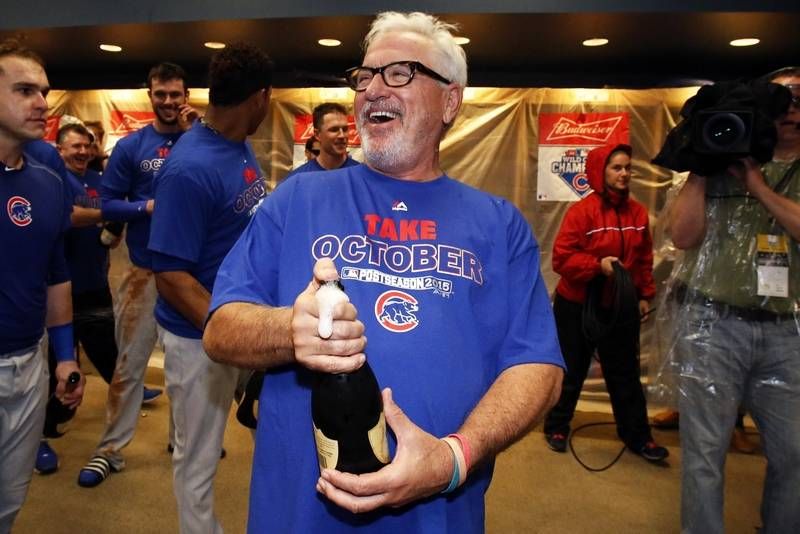

And then came this guy:

I'm a huge fan of Joe Maddon, and it's not just because of what he did with the Cubs. Anyone who can take the Tampa Bay Rays, whose identity can be summed up in the phrase, "wait, there's a baseball team in Tampa? Oh, St. Pete...who knew? Good for them" from never having had a winning season (ever) to three wins from a World Championship in three years is not a man to be trifled with. The moment I heard the Cubs had hired him, I knew it was an inevitability that they'd get over the hump and finally stop the madness. But what makes it such a compelling story is the way he did it. Some would credit his use of new-fangled statistics and analytics, which I begrudgingly admit are effective, even as they de-mythologize what is ultimately a game built on legends. (Legendary example: google the words "Curt Schilling bloody sock" and you'll be regaled with the Mary Shelley-esque story of the team doctor practicing an experimental surgery on a cadaver to 'be sure' sewing Schilling's ankle back together with a mere week to cut and recover would 'work.' Then see Schilling pitch the game of his life with sutures bleeding through his sock before a worldwide audience on the path to arguably the greatest comeback in baseball history, all things considered. Oh Red Sox, you never were so red. Now take that story and quantify it statistically, and watch the joy asphyxiate under a mountain of ugly numbers. But I digress.)

No, Maddon may be a statistical mad hatter, but I firmly believe that what put the Cubs over the top in 2016 was the dance party room. See, the Cubs' clubhouse was being renovated for the 2016 season and at Maddon's insistence, there was a room added whose sole purpose was to serve as a team gathering point. In this room, which was off limits to everyone except the players and coaches, there was a mandatory team dance party to commence immediately after every single win--and party they did. As I said at the start, baseball, like life, is a story built on seemingly infinitesimal wins and losses. If you're in the NBA and you win 82 games in a season, you have achieved perfection (yet it doesn't win you a championship somehow... the world is a strange place). In baseball, if you win 82 games in a season, you achieve the privilege of eating pork rinds on your couch while your betters play baseball in October. So before their playoff run even began, the Cubs' party room got used 103 times. For reference, they finished eight games in front of anyone else in baseball (meaning the next best team would have to beat them head-to-head eight in a row just to break even). Surely by that point the leather on the seats in there was beginning to wear, and they still had a postseason to play; yet it's impossible to ignore the psychology there, and the implications for how one's liturgical practices can shape an identity.

Doing the same thing every day is monotonous; there's no way around it. Doing the right thing every day is impossible, but even characteristically doing the right thing is tedious. And I'll admit, I'm the last person with any right to talk about doing the right thing every day. In all honesty, I'm more like the 1962 Cubs who lost 103, grinning my most blindly optimistic, pathetic grin and reciting the mantra "just wait 'til next year" (only to do it again four years later). But I'm still trying to find a way over that chasm between the man I am and the man I want to be, and the more I think about it, the more I realize that I have lost the sense of significance between winning and losing; between making the small, right choices day after day, and letting things slide and being ok with the loss. After all, each one is insignificant to the whole, for the most part--no cosmic failure will happen if I don't wake up five minutes earlier and stop to pray, and the kids won't remember whether I taught them a Bible lesson on a Wednesday night in May 2018 when they were five. My wife won't walk out because I left the kitchen a mess after dinner, and skipping dessert tonight isn't going to turn me into a glistening Adonis. Surely I will be there, ready to do the right thing when the big stuff comes along, right?

A personally painful moment in my baseball history was the 2011 September collapse of my beloved Atlanta Braves, known colloquially as "The eternal bridesmaid of the postseason--except when they played the Indians, Lord have mercy on that lot." The Braves were one month away from a postseason berth, just 27 games to go, and had an 8.5-game lead in hand on the St. Louis Cardinals. The Lord willed that Atlanta went 9-18 that month, and the Cards went 18-8, knocking off the Braves by one game. It's easy to point to that bad...bad...bad stretch in September (which included three losses in St. Louis) and say that's where their season was lost. But all other things being equal it could just as easily been saved back in April, when they lost two of three at home to the Cardinals. Turn a single game lost by a single run into a win, and the September collapse would have been judged a bad way to end a regular season, but not an out-and-out disaster. Let's face it--they would likely have crashed out of the postseason anyway, but there's a world of difference between getting shut down by the prettiest girl at the dance and not even having a ticket.

The point is that we never know the tipping point in our lives. Where's the line between who we are characteristically, and what's out of character for us? If we say the little moments don't matter, and live life accordingly, doesn't life become just a game of rationalizing why this particular moment is a little moment? That's a deep fear of mine, because it's a game in which I've become a ruthless expert. If we learn to see moments as small, can we really recognize when a big one comes? How do we know that nail-biter we lost in April won't be the lynch-pin that seals our fate in September? It is a bitterly ironic definition of futility that we try to selfishly indulge in life's moments by dismissing their significance. I can't help but be reminded of the parable Jesus taught where he's speaking to two men at the Judgement, and says (in my poor paraphrase) to the one: "I was naked, and you clothed me, hungry, and you fed me," and so on. To the other he says, "I was naked, and you did not clothe me, hungry, and you did not feed me," and so on. Both men respond with, "Lord, when did we see you?" And Jesus responds with, "As you did to the least of these, so you did it to me." The one did right without regard for who he was doing it to, and the other was looking for Jesus before he acted. Didn't see him? It must not matter. So much for the insignificance of little things.

If you'll pardon my breaking the gravity of those words, that takes me back to the party room. I think I get what was happening--every time there's an outcome, it should feel objectively different. Win, and you get a 30-minute rave. Lose, and you go back to noisy locker room filled with people asking you questions about your mistakes. Neither outcome is earth-shattering, but the one would never be mistaken for another. I read an article late in the 2016 season that over the course of the season, the character of the dance parties changed subtly: the players began to win so much they worried they'd get tired of the party room. And yet, they never did get tired of it--just try missing it for a couple days, and realize how much better it is to be there than not. Moreover, the party room was itself a training. Specifically, it was training them for this:

This is not a level of party that can be achieved on the fly--this was meticulously crafted and tirelessly rehearsed, specifically 113 times prior to commencement. As Christians, we too have an annual practice of the party room: the 50-day feast of Easter. It's notable that A) the feast of Easter is a full 10 days longer than the penitential season of Lent (the longest fast of the year), and B) it's a feast that comprises more than 1/8th of the entire calendar. It's a rehearsal for an eternal celebration. And yet, for the most part, it goes unnoticed beyond the day, or maybe the first week. I've tried to remember Eastertide in all its significance this year, but I confess it's with mixed results. I've been especially good at the indulging myself part, but characteristically lacking in the contagious expressions of love and joy part. I've been so busy excusing myself for the little ways in which I insist on living life according to my plan, my schedule, and my agenda, that I've excused myself from the party room. None of this matters if I can just convince myself that none of this matters.

This is not a level of party that can be achieved on the fly--this was meticulously crafted and tirelessly rehearsed, specifically 113 times prior to commencement. As Christians, we too have an annual practice of the party room: the 50-day feast of Easter. It's notable that A) the feast of Easter is a full 10 days longer than the penitential season of Lent (the longest fast of the year), and B) it's a feast that comprises more than 1/8th of the entire calendar. It's a rehearsal for an eternal celebration. And yet, for the most part, it goes unnoticed beyond the day, or maybe the first week. I've tried to remember Eastertide in all its significance this year, but I confess it's with mixed results. I've been especially good at the indulging myself part, but characteristically lacking in the contagious expressions of love and joy part. I've been so busy excusing myself for the little ways in which I insist on living life according to my plan, my schedule, and my agenda, that I've excused myself from the party room. None of this matters if I can just convince myself that none of this matters.

The feast of Easter ends this Sunday, and I've wanted to find a way to take it with me. In a way, every Sunday is a little Easter, but surely I can argue myself out of looking at it that way, right? There's so much that needs to be done before a Monday--dishes are piled up, I don't have any clean clothes, I'm way behind on songwriting and grass cutting and ah, forget it, let's just watch M*A*S*H. But then there's the emptiness that comes even while you do the thing you're doing. I read somewhere that the longer someone spends on the internet (in 2018, read: phone), two things happen to them: the more things they click, and the less time they spend on any one thing. Regardless of the specifics of the study, I've personally experienced its implications--what of this means anything? Is that important?--No, but maybe the next one. Nope, not that either.

But even a weekly trip to the party room doesn't seem sufficient when life is broken down into countless choices to either be celebrated or lamented in their own way. The Greek poet Archilochos coined the phrase, "we don't rise to the level of our expectations, we fall to the level of our training." The writer of the letter to the Hebrews in admonishing them for their immaturity in faith said that mature things were for those whose faculties were trained by practice to distinguish good from evil. Like the 2016 Cubs, if we don't practice celebrating victory like it's different from defeat (and it could not be more so), we will progress to the blindness of not knowing the difference, and finally the settled, passive nihilism that insists that the difference is negligible. And that, I believe is hell. Lord God, save me and anyone like me from such a state. I need to re-learn the practice of giving thanks and praise for every good thing--every choice to stop my all-consuming (but lest it come back to bite me, ultimately insignificant) schedule and say a prayer. Every kindness done to another, however invisible. The embodied lesson of love taught to my children in deliberately showing patience with them when I'm suffering. The thankless diligence at work, with full recognition that the only reward I'll ever see for it's on the other side of a tombstone. I confess, there hasn't been much of these in my life for a long time. I need to practice being in the party room. In the joyful celebration of a faithful life is found the only distinction from a waking death, and I've had enough of forgetting the difference. I want to practice the kind of victory celebration that makes a man do this:

Though, what's critical to remember in that video is, this is still the practice party. What's this guy going to look like at the real thing? I'm not sure, but Lord, let me be beside him.